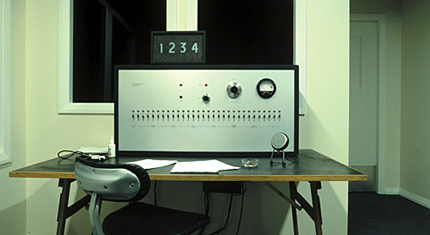

The "Teacher's" Station in the Original Milgram Experiment

The "Teacher's" Station in the Original Milgram ExperimentOne of the most famous psychological experiments of all time was the "Milgram" experiment performed at Yale in 1965. It was the aftermath of the war and many people were wondering how so many people could be complicit in the Holocaust. The point of Stanley Milgram's experiment was to test the relationship between authority and a person's willingness to inflict pain on a stranger.

The set-up was simple. Volunteers from New Haven were told they were participating in a study testing the effect of punishment on learning. When they arrived they were paid in advance and told the money was theirs to keep no matter what happeened. They were then paired with a shill. The shill and the participant supposedly drew lots to determine who was the "learner" and who was the "teacher." The draw was rigged so the shill always became the learner. The real participant was then placed in front on an impressive panel of switches labeled with successively highly voltages. The upper ranges of these voltages were marked with labels like "Extreme Intensity Shock," "Danger," and the last three switches, going up to 450 volts, simply had X's above them.

Switch Labels from Milgram's "Shock Generator"

Switch Labels from Milgram's "Shock Generator"The participant then watched as the "learner" was led away to an adjacent room and strapped to a chair and fitted with electrodes. The "teacher" was given a chance to feel what an electric shock feels like, then given a list of questions to ask. Each time the learner got one wrong, the participant was supposed to administer a shock. The first shock was the mildest and then the second would be one degree greater, etc.

As the test progressed, the shill-learner would deliberately get things wrong and cry out in pain when shocked. As the shocks got worse, they pretended to react even stronger. In the upper ranges they would complain of heart pain, ask to leave the test, and beg. Above 150 volts they would stop responding entirely--suggesting that they were either dead or passed out. If the "teacher" objected to the person in authority, the experimenter, he would respond with a scripted progression.

So the real test was how far would the participants go before conscience kicked in and they refused to shock further. The results: a whopping 80% of people continued delivering shocks even after the 150-volt threshold, additionally, 65% went all the way to 450 volts!

The reason this comes up now is that a researcher at Santa Clara, Jerry Burger, decided to replicate the experiment in 2008. Because of ethical rules now in place, he could only take participants to the 150-volt threshold so as not to scar them with the realization that they are capable of killing someone. Still, he found that 70% of modern participants were willing to shock to the 150-volt level.

Despite all the changes since the 1960's, the cold reality is that most people in America (and presumably in Canada, too) are willing to follow instructions even when that results in extreme pain or distress to others. Little wonder that we end up in situations like Abu Graib (Cf. the Stanford Prison Experiment) and AT&T customer service. Given the right circumstances, good people will do bad things. (As an aside, if you are unfamiliar with the Stanford Prison Experiment you will find it a fascinating example of how systemic evil operates, no one, not even people running the experiment, could escape doing terrible things.)

What to do? The article in the NY Times about Professor Burger's experiment suggests that knowledge of this effect may help promote vigilance against its affect. In fact, an instructor at West Point contacted Professor Burger to talk about how the results are being taught to military Officers.

-t

No comments:

Post a Comment